Idea Having is not Art

What AI is and isn't good for in creative disciplines

An artform is a framework for a relationship between the artist and the audience. Artist and audience are engaging in activities that are extremely different (e.g. hitting a piece of marble with a chisel in ancient Athens, vs. staring at the finished sculpture in a museum in New York two thousand years later) but they are linked by the artwork. The audience might experience the artwork live and in-person, as when attending the opera, or hundreds of years after the art was created, as when looking at a Renaissance painting. The artwork might be a fixed and immutable thing, as with a novel, or fluid, as with an improv show.

But in all cases there is an artform, a certain agreed-on framework through which the audience experiences the artwork: sitting down in a movie theater for two hours, picking up a book and reading the words on the page, going to a museum to gaze at paintings, listening to music on earbuds.

In the course of having that experience, the audience is exposed to a lot of microdecisions that were made by the artist. An artform such as a book, an opera, a building, or a painting is a schema whereby those microdecisions can be made available to be experienced. In nerd lingo, it’s almost like a compression algorithm for packing microdecisions as densely as possible.

Artforms that succeed—that are practiced by many artists and loved by many audience members over long spans of time—tend to be ones in which the artist has ways of expressing the widest possible range of microdecisions consistent with that agreed-on schema.

Density of microdecisions correlates with good art. A sculpture seems more marvelous to us when we consider the number of times the sculptor had to strike a chisel with a mallet in order to fashion it from a block of marble. But that alone doesn’t assure success; those microdecisions have to have been made in accordance with some kind of overarching plan for what the finished work is going to look like. In AI lingo, that’s called metacognition, and I’ll circle back to it later.

Each artform has its own set of conventions and constraints. For example, if I’m writing a sentence, I can choose from any word in the dictionary. But once I’ve made that choice I need to spell it correctly or else no one will be able to read what I’ve written. And there is a vast range of ideas that I could express in a sentence, but the sentence needs to be structured according to rules of grammar.

Notwithstanding all of those rules and constraints, there is still vast scope of possible things that a writer can say. Moment-to-moment decision-making is happening in some kind of intermediate zone between—at the more granular level—spelling words correctly (where there is only one correct choice) and writing grammatical sentences (more choices, but still somewhat rule-bound) versus—at the higher end—delivering a coherent manuscript hundreds of pages long.

That intermediate zone, where all of the decisions get made, is poorly understood by non-writers. Many published novelists, including myself, have stories about being approached by someone who “has an idea for a book” and who proposes that the writer should actually do all of the writing and then split the proceeds with the idea haver.

Moviemakers and architects, who understand the grammar of their artforms as well as I do that of the English language, must get approached by idea havers all the time. Sometimes they even get sued by idea havers who think, or claim to think, that their idea was stolen.

What idea havers don’t understand is that it’s in the making of all of the microdecisions that the actual work of creation takes place, and that without it the idea might as well not exist. Someone could approach Leonardo da Vinci and say “I have an idea for a picture of a woman sitting in a chair smiling enigmatically” but it would be worthless compared to the finished work, which is realized in the form of countless individual brushstrokes, each reflecting a microdecision on the part of the painter.

(I know nothing about painting, but I’m fascinated by palettes, which start out as basically digital—globs of pure colors dotted around a board—and become more and more analog as the artist mixes the edges of the globs together to create blends. That process, as well as choosing a brush, deciding where on the palette to touch it down, and where and how to apply it to the canvas, are examples of microdecisions that a gifted painter must make almost unconsciously.)

Fortunately for all of us, artists actually enjoy the process of making those microdecisions and fixing them into a framework. As a matter of fact, artists make it their life’s work to do just that.

The categorical error made over and over again by idea havers is to mistake the actual production of the artwork—the making and fixing of the microdecisions—for mere drudgery that can, and ought to be, done away with.

It is difficult to explain this to people who don’t automatically understand it, but an analogy might be as follows: someone walks into a gym where athletes are busy working out and says, “actually, all you’re really doing here is increasing the gravitational potential energy of some massive objects. That could be achieved much more quickly and easily by using a forklift.” What they don’t get is that the people who are lifting the weights (a) actually take pleasure in the experience, (b) enjoy the social milieu of the gym—hanging out with other people who like what they like—and (c) derive benefits in their physical and mental health from having lifted the weights.

Making and executing all of those microdecisions takes a lot of time, a fact that sets up a classic dynamic between financial/managerial types and artists. It is best summed up in this classic line from The Agony and the Ecstasy in which the pope is hassling Michelangelo about his slow progress on the painting of the Sistine Chapel.

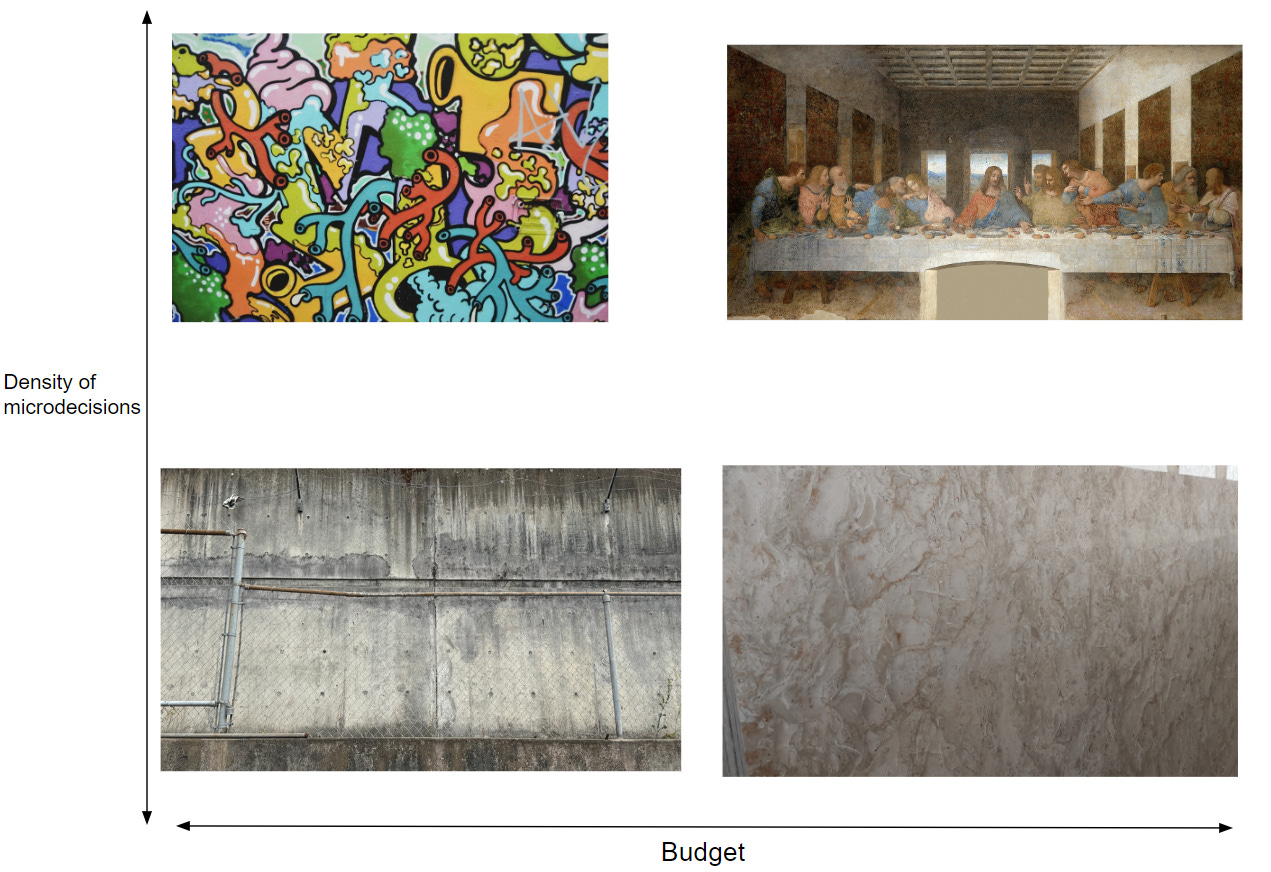

Since budget actually matters in many cases—we can’t all work for the Pope—here’s a grid for visualizing these tradeoffs.

The Grid (as applied to Decorating a Wall)

The vertical axis shows microdecision density, and the horizontal axis is budget. In this particular case I’ve chosen the artform “decorating a wall” but similar grids could be made for almost any kind of artform.

Or, putting names on the quadrants:

Utilitarian (lower left)

In the lower left, there’s no time, budget, or interest in having the wall look like anything other than what it is. No microdecisions get made, no artists are involved.

Prefab (lower right)

In the lower right, there’s budget available to make it look nice. But there’s an unwillingness, institutional or cultural, to leave it up to an artist.

Books could be, and have been, written about where that reluctance came from. Suffice it to say that until the Twentieth Century most buildings were decorated. Now they’re not.

Rather than entrusting the available budget to an artist, prefabricated materials are chosen by picking them out of a showroom display or a swatch book. In the example above, natural stone has been used. The details of how it looks are, in effect, left up to nature. The precise texturing of the surface was fixed by random geological events a long time ago.

High Art (upper right)

The upper right is what you get when the owner has both money to spend and a willingness to entrust an artist with the authority to make a large number of micro-decisions.

Punk (upper left)

The upper left is the natural condition of most actual creative artists: they know that no one understands them and that they’re not going to get funded. Some of those wither away and stop doing art. There’s no space for them in this grid. The ones who go out and make art anyway are embodying the ethos of Punk.

(I debated whether to use the term “Indie” instead of “Punk,” since indie filmmakers and game developers absolutely live in that upper left quadrant. My detailed reasons for using “Punk” will have to wait for a future post. For now, let’s just say I picked it because of connotations. “Indie” has connotations of artsiness and hipness. “Punk” connotes grit and defiance and a general IDGAF stance that I think is essential for survival in that quadrant. “Punk” is defined by positive acceptance and passionate embrace of a particular way of doing art whereas “Indie” seems to be a diagnosis of exclusion, defined by the absence of financial support.)

Application of The Grid to Movies and Games

The Grid can be applied to any artform, which I will leave as an exercise for the reader. It’s a better fit to some artforms than others. For example, writing words is so inherently cheap that budget doesn’t matter much. Writers are pretty accustomed to living in the upper left hand corner of the grid, and because it’s a solitary occupation that doesn’t require any equipment, one can easily pursue it with no budget at all.

The Grid applies very well, however, to movies and games—two artforms that, thanks to advances in game engine technology, are becoming more and more difficult to tell apart. What those artforms have in common is that you can’t make them without combining the work of creators from a range of artistic disciplines: actors, animators, sound designers, programmers, sculptors, art directors, and so on.

Each of those creators is making countless microdecisions in their particular artform over the course of the project’s development, which typically stretches over years. So, movies and games have extremely high microdecision density. Every pixel the audience sees on the screen was affected somehow by the work of dozens, if not hundreds, of different artists. Some of them, such as actors, couldn’t be more obvious while others, such as color graders, are practicing crafts that are no less artistically impactful for being incredibly arcane.

Unlike writers, the artists who practice movie/game artforms can’t do what they do without equipment and collaborators. Technology has eased those constraints quite a bit. Now you can shoot a movie using a phone and edit it using free software. The sound, lighting, and other details won’t be great, but that’s all totally consistent with the Punk ethos. Likewise, improvements in game engines and asset marketplaces make it possible for low-budget, small-team, Punk-quadrant game developers to make indie games that would have been impossible ten years ago.

So much for the upper half of the grid. Since AI systems, almost by definition, involve minimal human input, they are strictly lower half.

How AI relates to the Grid

AI systems churn through vast catalogs of existing art, breaking the results of past artists’ microdecisions into tokens that, in response to a human-supplied prompt, can be statistically recombined to generate texts, images, videos, sounds, or what have you. The result is an artwork that appears, at least at first glance, to have the same microdecision density as one that was made through traditional processes. It looks like it belongs in the upper tier of the grid. But in truth the number of microdecisions made by the human who issued the prompt is very small—about as close to the bottom of the grid as you can get.

Is it lower left or lower right, though? Low budget or high budget? That question is still in abeyance. You can access these models for free, which makes it low budget for an individual user, but developing them is extremely expensive and seems to be consuming hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars. If the sole function of AI systems were to generate artwork, it would almost certainly be the highest-budget art ever made.

Conclusions

What AI art can’t do

Since the entire point of art is to allow an audience to experience densely packed human-made microdecisions—which is, at root, a way of connecting humans to other humans—the kinds of “art”-making AI systems we are seeing today are confined to the lowest tier of the grid and can never produce anything more interesting than, at best, a slab of marble pulled out of the quarry. You can stare at the patterns in the marble all you want. They are undoubtedly complicated. You might even find them beautiful. But you’ll never see anything human there, unless it’s your own reflection in the machine-polished surface.

Last week I was in a room where Bill Gates addressed founders and investors interested in AI. He spoke about the need for AI systems to develop metacognition. This basically means thinking about what they are thinking about. It’s needed in order to generate more coherent and goal-directed results. It also can make these systems much more efficient.

Artists do metacognition as a matter of course. When I’m writing a book I’m always thinking about the overall plot in the back of my mind, even when working on it at the most granular level, writing out the letters one by one. The painter making a tiny streak of paint on the canvas knows how it relates to the overall picture.

If AI systems were better at metacognition, they might be better, or at least more efficient, at generating coherent works of art. But the audience would still be relating to a computer algorithm, not a human being.

Suggestions for people in the AI industry as to how to address art and artists

Provide fine-grained control over tools

When a sculptor uses a chisel to shape marble instead of clawing at the stone with his fingernails, or when a painter uses a brush instead of smearing paint around with his bare hands, we don’t deprecate the chisel or the brush, and we don’t think less of the artist for using them. They’re just tools that give the artist more agency to put their microdecisions into effect. They don’t take decisions out of the artist’s hands.

Some artforms are more tool-intensive than others. Writers, for example, need very little in the way of tools, but even we can geek out over fountain pens. Sculptors, painters, metalworkers, and woodworkers put a lot of energy into creating and adapting the tools that are in their hands every moment they are working. In general it’s important for artists to be able to craft their own tools. To get an idea of the vibe, watch this video from Radoslaus, an armor maker in Poland, in which he makes a special-purpose hammer for a specific project.

In general artists are going to be more comfortable with AI-driven tools if they can customize and learn how to use them at the highest possible level of granularity. This increases microdecision density and makes for better art.

Give credit, visibility, and compensation to the artists

For some reason, YouTube recently dropped into my feed a cluster of videos from a few years back, all based on a sea shanty called The Wellerman that was originally performed by Nathan Evans. This turned into a viral phenomenon that spun off many remixes as other musicians added in their own vocal and instrumental tracks. Here’s one such video, and if you click on that one you can find a lot more.

Of note is that

these musicians were able to quickly and cheaply self-organize around a project they found interesting

it is all very low-tech; many of the singers are just using cheap wired earbuds and holding the microphones up in front of their faces

you can see their faces and get some sense of who they are. They look like they’re enjoying themselves!

I doubt that this project made much money for anyone. How to route revenue to contributors is a separate topic I won’t try to get into here. But it begins with visibility and credit. No artist wants to see their work run through a blender by an AI system and served up in a slurry.

Enough with all of the image posting

I understand that AI developers are very excited about the capabilities of their systems and that they are striving for some kind of competitive advantage, trying to raise money and so on. Posting images and videos made by AI systems might seem like an effective way to do show off and gain an edge. That might be true for a certain narrow technical audience, but for artists and art lovers it’s like staring at a slab of polished rock and being told that this is going to replace you and what you love.

Don’t dance on the graves of artists’ careers

I think this one is self-explanatory, but there is a really distressing tendency on the part of some hard-core AI advocates to show a kind of triumphalist attitude towards the creative industries, which they think have been somehow vanquished by the forward march of technology. Knock that shit off! Most artists have already been plenty vanquished and don’t need any more vanquishing. Getting vanquished by billionaires is a bad look, especially when it’s evident that these systems were trained on the work of artists who aren’t being credited or compensated.

A pleasure to read and ponder. Maybe an additional path - the Greek root of poet is "maker". It's not the idea, it's the doing and the resulting expression that maketh the maker.

I make furniture. It’s NOT my day job but I’d love for it to be. Part of the making of the furniture involved inventing a system of hardware to hold it together.

But most of my furniture making really in loves more design work than making because my parts are mostly made by really clever machines that do some version of CNC.

Because of this I am hesitant to call myself an “artist.” “Craftsman” maybe? “Designer” certainly. And yet my pieces have been in art galleries. But while I make lots of “micro decisions” during the design process, once the actual furniture is getting built (one might call it “making license plates,” I suppose) I have robots do the labor. Although I suppose NS doesn’t personally print all the books he writes so maybe that’s comparable?

If you go see some of Donald Judd’s installations in Marfa, TX you’ll find out that he had various parts made in factories and then much of the assemblies were made by people who worked for him. But it seems like Judd is an “artist” to me.

One thing computer-aided (stress on the word “aided” here) has done, I think, is unlocked a lot of creativity from people who don’t have decades of experience honing a craft. It gives access to “idea-havers” to enter the world of (“artist”? “maker”?) with less experience than would have been required in the past. I’m still not sure how to feel about it - even in my own pursuits.

I DO think it will lead to a premium being put on work actually made by human hands. When I think about this I usually think immediately about the Sandbenders laptop case discussed in “Idoru” by William Gibson or to the paper-maker and other craftspeople to be found working for the Vickies in “Diamond Age.” In a weird way, the flaws found in works made by actual human hands will make those objects more valuable I suspect.

Anyway, I’m not doing any “AI stuff” but there sure is a great big grey area in which I find myself and I feel like this article helps me explore it a bit.