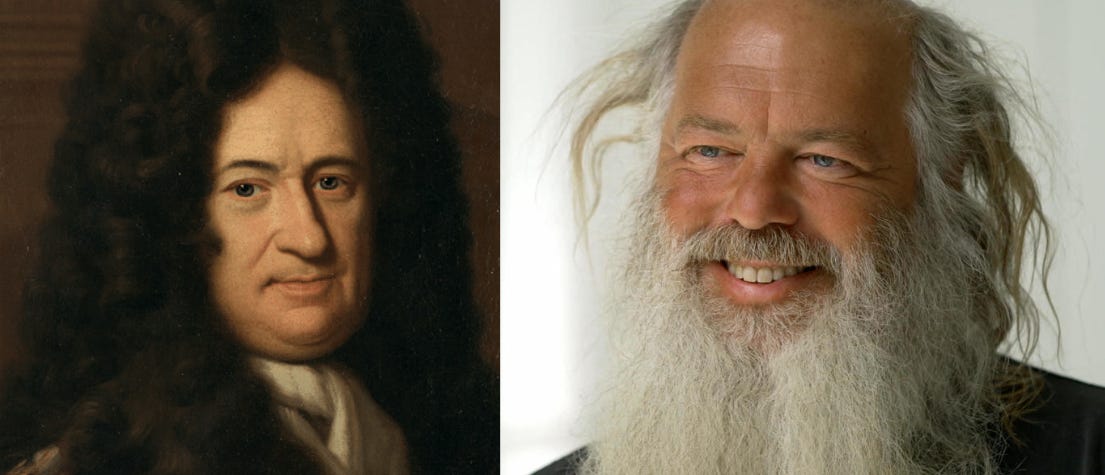

A few months ago, in the wake of a talk that I had delivered at DICE (a game industry summit conference), Rebecca Barkin sent me a link to some remarks by Rick Rubin.

(For those of you who are as instinctively link-phobic as I am, just know that the DICE talk is 20 minutes long. So I’m going to summarize key points farther down in this post. But if you watch the Rick Rubin link for a mere minute and a half (48:57 to 50:30) you’ll get all that matters)

My thesis is that Rebecca, Rick, and I are all circling around the same idea, which is central to Graphomane. My overall topic here is the intersection of tech and art. But tech costs money, and so this ends up being about the business of art and how it does or doesn’t get financed, and the hijinks that ensue when money people and creators try to get along with each other.

My first post on Graphomane was on the topic of how OpenAI had created a soundalike Scarlett Johansson voice for their product. I chose that because it so sharply delineated the fault line between the tech/business mind and the creative mind.

Another such fault line lies in financialization, which is the incentive structure that drives decision-making among people concerned with money. To use Rick Rubin’s phrasing, it’s focused upon outcomes. Which is to say, things that might happen, or that are expected to happen, in the future.

Now, in most areas of human endeavor, if you’re smart and well-informed enough to make better guesses about what is likely to happen in the future, then you can reap profits, provided that there are financial instruments in place enabling you to place bets on your guesses. Historically, this way of thinking breaks the surface at least as early as the Code of Hammurabi, which includes rules about moneylending. Moneylending’s the simplest and most obvious form of financialization. It basically consists of making educated guesses as to which borrowers are most likely to pay you back. And it has only become more sophisticated since Hammurabi.

Though financial mechanisms can become mind-bogglingly complicated, at the end of the day they are all based on principles that are so obvious, at least to money-minded people, that they don’t even seem worth spelling out. If I’m good at predicting outcomes, I can get rewarded. And deserve to be.

That’s why it’s funny— and, in a way, mind-blowing—when Rick Rubin describes that outcome-based mindset as something to which there is an alternative.

And the alternative, which seems just as obvious to him as stocks and bonds do to a Wall Street quant, is to create a thing.

This isn’t just starving artists whining about how no one understands them. An extremely successful Hollywood movie producer once explained to me that, at the end of the day, their job consisted of delivering money into the hands of a director and then keeping the financiers from meddling with the process long enough for the director to finish the film. The results, for this one producer alone, have been worth billions.

So there are huge businesses constructed on the way of thinking and working that Rick Rubin is describing. Rubin personally is a centimillionaire. The artists he’s worked with have generated billions in economic activity.

In a sense, though, such statistics just make the whole picture even more perplexing to outcome-centric money people.

During a 60 Minutes interview, Anderson Cooper goes to the heart of the matter by flat-out asking Rubin what he’s being paid for. Rubin’s answer comes down to that he has taste.

So, in a world where it’s demonstrably the case that intangibles such as taste can generate billions of dollars in economic returns out of basically nothing, what’s a financier to do?

Rebecca Barkin is a co-founder of Lamina 1, which is a blockchain we’ve been establishing to support creators of an open, decentralized Metaverse. Together we’ve learned a lot about crypto—not just the technical aspects of how modern chains work, but also the culture of that industry. That culture is strongly skewed toward financialization. Which makes perfect sense, given that the initial applications of blockchain technology all had to do with creating currencies.

In the Scarlett Johansson/OpenAI post I talked a little about the word “fungible,” which most people today first encountered when they saw it in the phrase “non-fungible token” or NFT. Units of currency, be they dollars or bitcoins, are the very definition of fungible. That’s the whole point of them. Fungible tokens—the digital equivalent of coins—can be minted on blockchains. There is a whole financial industry built on that kind of money.

But you can also use a blockchain to mint a non-fungible token. That is how we get the NFT industry, which is essentially an online art market. As the name implies, each NFT is unique. They’re not interchangeable in the way that currency tokens are. So strong is the pull of financialization, however, that there has been a tendency to use NFT collections as investment vehicles. If you buy an NFT not because you like it but because you’re hoping you’ll be able to sell it for a higher price later, then you’re engaging in speculation as opposed to art collection.

Rebecca and I were talking about such things last year when she summed it all up by saying “You can’t architect a compelling experience backward from a desired financial outcome.”

I liked the phrase enough that I wrote it down. It was not until months later that we came across the above-linked video of Rick Rubin saying much the same thing, likewise stressing that word “outcome.”

I quoted Rebecca in the above-linked DICE video, and added my own line “Premature financialization is the root of all evil.” That’s a little bit of a nerd in-joke, adapting a famous computer programming dictum by Donald Knuth.

The heart of my argument is that in any market, be it for physical or virtual (i.e. online digital) goods, intangibles have actual economic value. Intangibles keep the bottom from falling out of markets. Probably the clearest example is old books that you might have lying around your house. No matter how beat-up these might be, they actually do have a market value, in the sense that you might be able to get at least a few pennies for them if you piled them all into a milk crate and dropped them off at a used book store.

But you don’t do that. You keep them in your house anyway because a beloved old book has intangible value far exceeding its liquidation price.

The worldwide market for used books has a certain dollar value that would immediately collapse if everyone decided to liquidate their collections all at once. What keeps it afloat is, for lack of a better word, taste.

Applied to the market for virtual goods—the odds and ends that people accumulate in their video game inventories, for example—what this means is that value can be created and preserved in those markets by imbuing those items with intangible value. For me personally as a video game player, that’s a combination of two things: the memories I have of acquiring those items during gameplay, and the aesthetic qualities attributable to the artists who created them.

Both of those fall within the purview of game developers. I don’t have good memories of playing the game unless the game is fun and engaging—which doesn’t happen by accident. And the objects aren’t beautiful unless game artists use their talents and taste to make them so. “Fun” and “beautiful” are not adjectives that lend themselves to financial analysis.

One good book for learning about the development of the financial industry is Against the Gods by Peter L. Bernstein. In it he mentions “Leibniz’s Admonition,” contained in a 1703 letter from Leibniz to Jacob Bernoulli.

“Nature has established patterns originating in the return of events, but only for the most part.”

He and Bernoulli were talking about what we’d today call probability. Leibniz is saying that you can predict events from natural laws and from past experience, but only up to a point. There are always outliers—and in some cases those can be very important.

It could be that what creators are doing is patrolling the edges of what can be understood and predicted. And that the only way to operate in that space is to develop a conception of what might be, and to realize it. Otherwise, you’re just generalizing from past data, and you can’t create anything new.

Some readers might see in that last sentence a connection to Large Language Models and what they are, and aren’t, capable of. I’ll get on to that in a later post.